Algorithms I - General Introduction

in CS 101

Definition: an algorithm is a finite sequence of unambiguous and effectively computable instructions that produce some intended result.

Let’s explore some of those terms in more detail:

- finite: an algorithm must terminate at some point. If it might go on forever, then we might never achieve the intended result.

- sequence: the steps are ordered (first do this, then do that, etc.) and the order (in most cases) must be followed to achieve the correct result.

- unambiguous: each step must be clear. There can be no confusion as to what must be done. If multiple interpretations of the instruction are possible, it’s not an algorithm.

- computable: each step must specify some task that can be performed. This gets a little theoretical, but there are some types of problems that no computer can solve in finite time. For now, let’s try to “predict tonight’s lottery numbers.” Because the lottery is random, there’s no algorithm we can create/follow to reliably predict it.

- result: we develop an algorithm to reach an answer/output/end state, or else, what’s the point?

In computer science, most algorithms are intended to be implemented as computer programs. However, keep in mind that an algorithm is, simply stated, a step-by-step process. Therefore, algorithms can be implemented by different means. For example, the human brain calculating the sum of two numbers or an insect searching for food.

Example 1: An algorithm for calling a friend on the telephone

1. Pick up the phone and listen for a dial tone

2. Press each digit of the phone number of your friend on the phone

3. If busy, hang up phone, wait 5 minutes, jump to step 2

4. If no one answers, leave a message then hang up

5. If no answering machine, hang up and wait 2 hours, then jump to step 2

6. Talk to friend

7. Hang up phone

The above algorithm makes the following assumptions

- Step 1 assumes that you live alone and no one else could be on the phone

- The algorithm assumes the existence of a working phone with active service

- The algorithm assumes you’re not deaf or mute

Example 2: An algorithm for deciding what to wear based on the temperature outside

1. if the temperature > 75 /* it's hot out */

put on tshirt,

put on shorts,

put on sandals.

2. else if temperature > 60 /* it's warm out */

put on blue shirt,

put on blue jeans,

put on white socks.

put on sneakers;

3. else /* it's cold out */

put on sweatshirt,

put on blue jeans,

put on wool socks,

put on shoes,

put on jacket.

The above algorithm assumes that you have all identified articles of clothing.

Try it yourself: Pick an everyday or interesting task and create an algorithm that explains how to do it.

Note: when creating an algorithm you are allowed to be somewhat vague without being imprecise. This is shown in example 1 (calling a friend) where I say to “leave a message”, but not what that message is. Naturally, this would be dependent on the individual call and does not affect the actual process of making a call. Reasonable assumptions assume the presence of the necessary materials. Unreasonable assumptions introduce ambiguity that may make it difficult to get to the intended result (for example, assuming universal knowledge of much a “pinch” of salt is).

Pseudo-Code Notation

Algorithms can be specified for either or both of the following audiences:

- for a computer to execute

- for a human to read/understand.

One notations often used for algorithms is called pseudo-code (aka false or fake code). Unlike real code which is implemented in a programming language and executable by a machine, pseudo-code cannot be executed directly by a computer. This is because it’s based on English (with little to no mathematical notation) and therefore easier for untrained humans to understand. In summary,

- Pseudo-code is not directly executable by a machine by fairly easy to translate into a programming language

- Pseudo-code is precise, but fairly easy for the untrained human to understand

- Pseudo-code is based on a natural language such as English, Spanish, German, and any language that humans speak/read/understand.

Below is an example of an algorithm, written in pseudo-code, that will compute the factorial for a given integer N. (The factorial is the result of multiplying all the numbers between 1 and *n, so the factorial of 4 (also written as 4!) is 1 x 2 x 3 x 4 = 24).

Example 3: an algorithm for finding the factorial of N.

1. Let N be an integer > 0.

2. Let K be 1.

3. If N = 1 then output K and stop.

4. Set K to K * N.

5. Set N to N–1.

6. Go back to step 3.

To understand this algorithm, we need to first understand the concept of a variable in programming. We use variable is mathematics too, but they’re a little different. In mathematics, a variable is a letter given to represent a value, like x = 5. However, in programming, a variable is a name given to a location in memory, which can hold a value. Another difference, is that the value in memory can be updated, whereas in mathematics, x = 5 means that x equals only 5 under any and all circumstances (of a given equation).

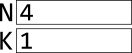

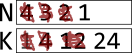

Using the idea of variables of memory, we can follow this factorial algorithm by specifying the value of N, as long as it obeys step 1 (N is greater than zero). This is a kind of input instruction. Let’s say N = 4, so the algorithm will compute the factorial of 4. In step 2, we encounter variable K, but the algorithm says it’s value (that is, K = 1). In memory, here’s what that looks like:

Step 3 asks whether N = 1. N is 4, 4 does not equal 1, so we skip the rest of that instruction.

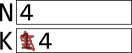

Step 4 updates a variable. We first compute the value of the expression K * N = 1 * 4 = 4, and then we update K (replacing whatever was there before) with the result 4:

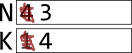

Step 5 updates another variable. We first compute the value of the expression N - 1, which is 4 - 1 = 3, and then we write that result to the box labeled N, replacing whatever was there before:

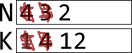

Step 6 says to go back to step 3. In step 3, does N equal 1? No, so we skip to the next instruction and continue. In step 4, K * N = 4 * 3 = 12. In step 5, N - 1 = 3 - 1 = 2:

Back to step 3: does N equal 1? No, so we go through the next instructions, updating the values of the two variables:

Back to step 3: does N equal 1? Yes, this time it does. So in step 3, we output the value of K and stop. By following this algorithm, we have just computed the factorial of 4:

Output: 24

Using the same algorithm with a different value of N, we could compute the factorial of any whole number greater than zero.

Try it yourself: Here’s an algorithm you can try tracing yourself.

1. Let A,B be integers > 0.

2. If A = B then output A and stop.

3. If A < B then set B to B–A and go back to step 2.

4. Else set A to A–B and go back to step 2.

- Try starting the algorithm with A = 35 and B = 21.

- What happens if A = 28 and B = 12?

- Finally, start the algorithm when A = 14 and B = 33.

Do you see the pattern? What does the algorithm compute?

Images, examples 3 & 4, and definitions by Prof. Christopher League liucs.net